Nancy Toney was born in Greenfield Hill, Fairfield County, CT around 1774 and resided there until she moved to Windsor in 1785. She remained in Windsor until her death in 1857 at age 82. Connecticut law dictated that the children of enslaved women were enslaved at birth, and thus Nancy began her life forced into enslavement, the daughter of two enslaved persons, Nanny and Toney.1

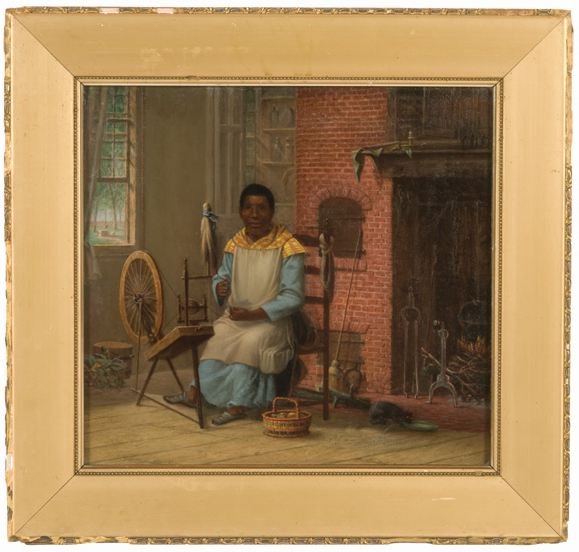

By 1785, Hezekiah Bradley of Greenhill, Connecticut had enslaved Nancy and when Bradley’s daughter, Charlotte, married Dr. Hezekiah Chaffee, Jr. that year, Nancy was moved to Windsor to live with the Chaffees. Dr. Chaffee Jr.’s 1821 will bequeathed Nancy to his daughter, Abigail Chaffee Loomis.2 At some point between 1840 and her death in 1857 and while she lived in the Loomis household, Nancy sat for a daguerreotypist who made a photographic image, her portrait.3

The United States Census documents Nancy’s status—as reported by the Loomis family—changed from slave to free person sometime between 1821 and 1830.4 Local histories name Nancy Toney as one of the last slaves in Connecticut.5 US Census records include Connecticut returns showing 25 persons counted as slaves in the 1830 Census.6 The 1840 Census lists 17 enslaved persons living in Connecticut.7

Gradual abolition laws in Connecticut applied to slaves born after 1784. Older Connecticut slaves, including Nancy Toney, were forced to rely on their owners for emancipation until Connecticut law prohibited slavery in 1848. It is unclear why Nancy Toney chose to continue living with the Loomis family after being named a free person in the census and after the abolition of slavery in Connecticut.8 Manumission papers documenting her freedom have not been found. Local lore contends that Nancy suffered disabilities preventing gainful employment.9 Emancipation laws required an enslaver to pledge that once emancipated, this formerly enslaved person would not seek assistance from the local poor relief system. Perhaps the Loomis family could not make this pledge and, yet, they considered Nancy Toney a free person. Evidence of Nancy’s opinions on this tenuous freedom remains elusive.

After Nancy’s death in 1857 at age 82, the Loomis family placed a headstone at her grave in Windsor’s Palisado Cemetery. The epitaph reads, “Born a Slave to/Hezekiah Bradley/on Greenfield Hill, Conn. was for/many years in the family of/Col. James Loomis by whom/this monument to her fidelity/is erected 1857.”

Systemic inequities would have bounded freedom for any woman of color, formerly enslaved person, and any member of the working class during the antebellum period in Connecticut. Freedom understood by any of these groups was more ambiguous, located somewhere between the full political and economic freedom of white property-holding males and the perceived material unfreedom of all enslaved persons.10 Black working class women’s experiences lived at the intersection of many implicit biases present in American society; prejudices that created real obstacles to economic autonomy. Nancy Toney’s life had been shaped by enslavement in the Chaffee family. Slavery prevented her from gaining education, additional job experience, and from sustaining relationships within her own birth family. However, it did not have access to take away Nancy’s interior life; a place where she was free to think, free to create her own sense of self, and her own life story.

1.Christina Vida, Nancy Toney’s Lifetime in Slavery - Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project. 2016.

2.William H. Chaffee, The Chaffee Genealogy, 1635-1909, New York: The Grafton Press, 1909, 205.

3. Karen Parsons, “A Portrait of Nancy Toney”, A Portrait of Nancy Toney | Loomis Chaffee Archives. 2020.

4."United States Census, 1820," Database with images. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 15 July 2021. Citing NARA microfilm publication M33. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.; "United States Census, 1830," Database with images. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 15 July 2021. Citing NARA microfilm publication M33. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

5.Henry Stiles, The History of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut. New York: C.B. Norton, 1859. 491. The history of ancient Windsor, Connecticut : Stiles, Henry Reed, 1832-1909 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive; “The Freedom Trail Runs Through Windsor” Windsor Historical Society News, September 1996, 3; “Concentrated History in Windsor” in “Complicity: How Connecticut Chained Itself to Slavery”, A Special Issue of Northeast, The Sunday Magazine of the Hartford Courant, September 29, 2002, 25.

6.Clerk of the House of Representatives, Abstract of the Returns of the Fifth Census. Washington, DC: Duff Green, 1832, 1830 Census - Full Document, 7.Doc No. 263, 23rd Congress 1st session.

7.Christopher Klein, “Deeper Roots of Northern Slavery Unearthed”, February 5, 2019, Deeper Roots of Northern Slavery Unearthed - HISTORY.

8.Marie K. Shanahan, “First Town Fracas: Centuries Later the Wethersfield-or-Windsor Question is Still Unsettled.” Hartford Courant, October 27, 1996.

9.Stiles, 490. The history of ancient Windsor, Connecticut : Stiles, Henry Reed, 1832-1909 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive; “Slavery in Connecticut from Historical Sketches by Jabez H. Hayden, 1900” Windsor Historical Society News, March 1993, 6.

10.See Jarden Hardesty, interview with Liz Covart, Ben Franklin’s World, podcast audio, May 24, 2016. Episode 083: Jared Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery in Colonial Boston - Ben Franklin's World (benfranklinsworld.com).

Nancy Toney

Portrait of Nancy Toney, attributed to Osbert Burr Loomis, circa 1862, Loomis Chaffee Archives.